The precocious activist group Greenpeace is often fond of touting sharp statistics and alarming mathematical models to back up its habitual threats against seafood companies and retailers. A hundred million sharks are caught each year in “bycatch” they insisted recently. Global tuna fisheries will go extinct, they declare, if current fishing methods continue. Some formula, known only to them, enables Greenpeace to assemble a ranking of seafood retailers and their sourcing methods. Do things our way, Greenpeace demands, because the numbers we are parading are unassailable.

“Trust us,” Greenpeace is effectively saying to the press and public, and never mind that our sweeping assertions aren’t backed up by any measurable data or peer review. But just take a look at a press release that the group put out a few days ago, one that’s actually based on hard data, to see how far they are willing to go to deceive people with statistics.

“Greenpeace’s Video Game Shark vs. Mermaid Death Squad reaches millions,” the release, which was distributed nationally, announces. If you haven’t heard about their game, don’t feel bad — few did. It was a simplistic knock-off of the Pac-Man game that cast sea creatures as the good guys and tuna companies as the bad guys.

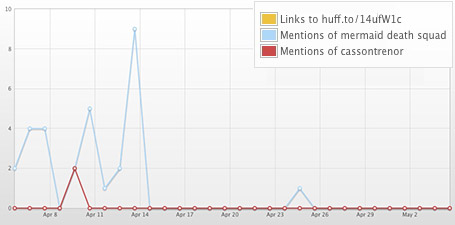

The game “was shared with two million viewers,” Greenpeace declared in the lead of the release. But this is almost certainly an outright falsehood. Greenpeace promoted the game mostly on Twitter but, as the chart right below from the Twitter analytics service Topsy shows, very few people cared to talk about it. As you can see, in the month following the game’s release, the game’s name was mentioned less than 30 times, while the Huffington Post article link wasn’t shared at all. So, two million viewers? Not even close.

CHART: In month after release, minimal Twitter chatter of Greenpeace game and coverageÂ

Greenpeace appears to be adding up the followers from the few individuals that did tweet about the game, along with the circulation of the few blogs that mentioned it, and then pretending that is the actual, total number of people that “viewed, played, and shared” the game. But as any advertising or social media professional would well understand, the number of potential people exposed to a particular item — which is called “impressions” — is a far different thing from the number of people that actually engage with the item, say by reading it or clicking on it. The average click-through rate in online advertising is about two percent at best and the rate at which people re-tweet an item is less than one-tenth of one percent. Â Greenpeace is actually assuming an even further step — that people saw the item, clicked through, and then actually took time to play their game.

But don’t take our word for it! There’s an easy way for Greenpeace to show whether they are telling the truth in their press release. They can make public the raw data from the webpage where the game resides.

It’s doubtful that Greenpeace will have the integrity to come clean. But here’s a more important question for the rest of us — members of the seafood industry, retailers, journalists, and consumers. If Greenpeace can’t even be trusted to tell the truth about something as straightforward and measurable as their website traffic, then why would anyone believe what they have to say about the science and data around sustainability?